I Read Less News Than I Used To

And That Says Something

I read less news than I used to. Not because I’m less curious. And definitely not because the world is calmer. If anything, it feels more complex, more fragile, and more interconnected than ever.

I read less because it started to feel less useful.

Somewhere along the way, staying “on top of the news” stopped feeling like staying informed. More noise than signal. More interpretation than information. I still skim headlines. I still want to know what’s happening. But the daily habit that’s mostly gone.

When I talk to friends and colleagues, many say the same thing. We consume less, not more, even as access explodes. That is not a content problem. It’s a trust signal. And not a good one.

What changed?

It’s tempting to say the problem is bias. That’s the popular answer. But I don’t think bias is the real issue.

Bias has always existed in news. Perspective is unavoidable. Editors choose what to cover. Writers choose what to emphasize. Readers interpret through their own lenses. None of that is new, and none of it is inherently bad.

What is new is opacity.

Today, it’s increasingly hard to tell where facts end and framing begins. Two articles can report the same event accurately and still leave readers with completely different conclusions. Not because one is lying, but because word choice does the work. What’s emphasized matters. What’s omitted matters even more.

All of it shapes perception.

Historically, editors balanced it through judgment, norms, and time. Today, speed, algorithms, and engagement economics overwhelm both. Humans are still in the loop, but the loop is moving faster than they can reasonably manage. And over time, that erosion adds up.

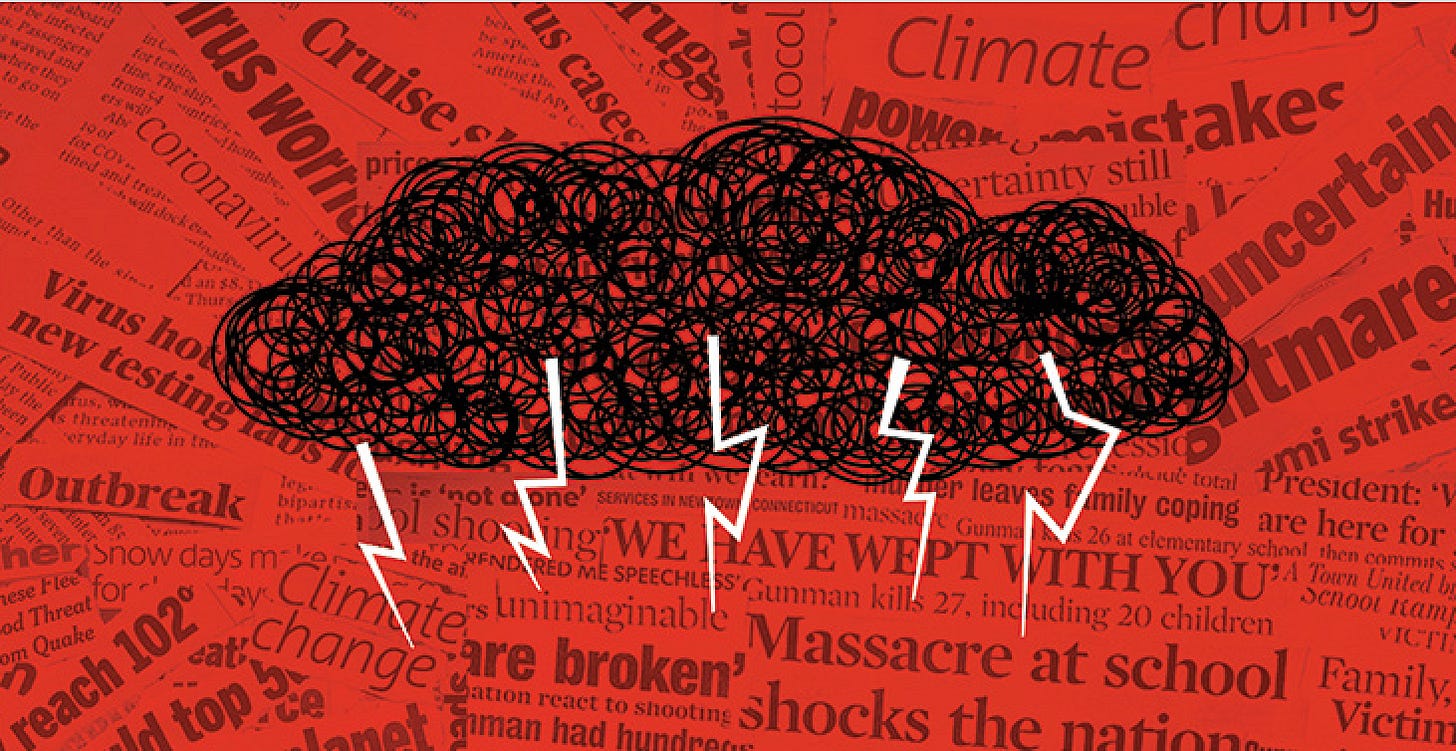

Why reading the news feels exhausting now

Here’s what I’ve noticed in myself. Almost every article seems to want me to feel something before it wants me to understand something. Anger. Fear. Outrage. Vindication. Even hope is packaged with urgency.

That emotional tax compounds. Over time, you start asking a simple question: is this making me smarter, or just more reactive?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. Machines already shape how we consume news. Algorithms decide what surfaces. Headlines are optimized for clicks. Feeds reinforce patterns of engagement. Whether we like it or not, AI already influences information flow. So the question isn’t whether AI belongs in news. It already does.

The real question is whether AI can help clarify rather than amplify. Can it separate facts from framing? Can it expose structure without enforcing ideology?

What AI is actually good at here

AI does not understand truth the way humans do. That’s important to say clearly. But it is exceptionally good at recognizing patterns in language and coverage. It can identify emotionally loaded terms. It can measure sentiment toward specific people or groups. It can track who is quoted, how often, and in what role. It can compare how different outlets frame the same event. And it can do this consistently, repeatedly, and at scale.

For example, a system can observe that coverage of a policy consistently highlights economic risk but rarely discusses social outcomes. Or that official voices dominate while community voices are missing. Or that language subtly shifts depending on who is in power. These are observable signals. Surfacing them is where AI adds real value.

A useful system should be able to say why an article leans a certain way. It should point to language choices, source selection, framing decisions, and omissions. It should show its work.

Once you can detect and explain framing, the next question is inevitable. Should AI do more than that? There are reasonable options, each with tradeoffs.

One approach is language normalization. The article remains intact, but the system highlights emotionally charged phrasing and suggests neutral alternatives while preserving factual meaning.

Another is contextual augmentation. The article stays exactly as written, but readers can expand background, historical context, or commonly cited counterpoints.

A third is comparative framing. Readers can see how the same story is covered across outlets, or view a synthesized summary that highlights differences in emphasis.

This is not a silver bullet. Models learn from existing language, which reflects social and cultural imbalances. Without continuous auditing, systems designed to expose bias can quietly introduce new distortions while claiming objectivity.

The question I keep coming back to

What if the goal of news wasn’t just to inform or persuade, but to help people think more clearly? What if, instead of asking “do I agree with this,” readers could first ask, “how was this constructed?” And maybe, if we get it right, reading the news can feel useful again - not because it tells us what to feel, but because it helps us see more clearly.